-

22-01-2023

Same Cascadia, New Management!

-

16-04-2025

How the Trade War Could Affect Your Business Book: 10 Questions Answered

-

03-12-2024

Platform, Patience, Proposal: The Three Keys to Traditional Publishing Success

-

26-11-2024

NEW PODCAST: All About Writing with Bennett R Coles & Sara Dahmen

-

29-05-2024

The Inevitable Journey of Ghazanfar Iqbal: Expatriate, Entrepreneur, and Author

-

04-04-2024

Publishing for Peace: Author Ben JS Maure Inspires Canadian Peacekeepers

-

30-11-2023

Unleashing Literary Flames: Award-Winning Author TK Riggins Keeps Readers Coming Back for More with 7-Book Series

-

15-11-2023

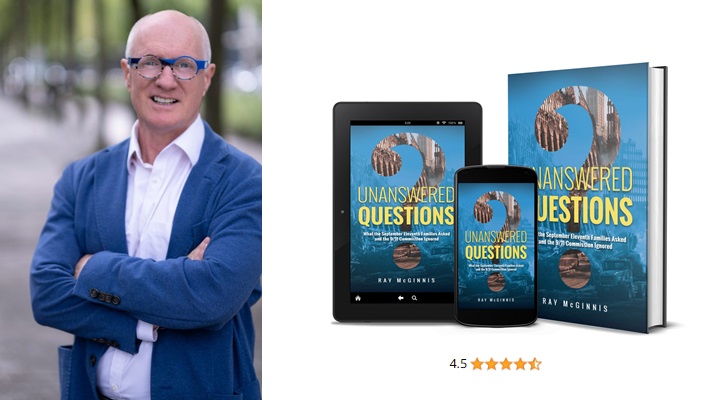

Author Ray McGinnis Reaches an International Audience with 100+ Interviews in 2 Years

-

14-11-2023

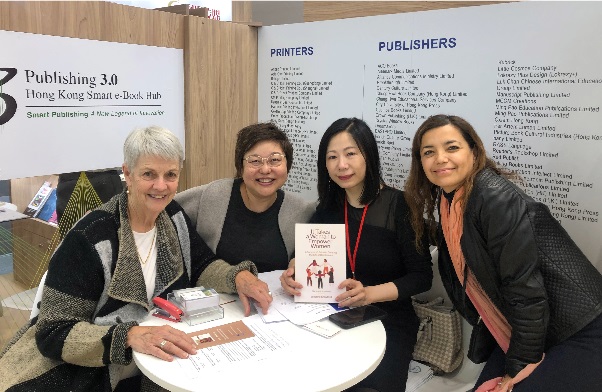

Books Without Borders: Launching Johanna Crawford’s Book at Frankfurt Book Fair 2023

-

12-10-2023

Pastor Owen Williams launched his book as a #1 bestseller and reached 450k+ people

-

24-04-2023

Mastering the Art of Analogies: Examples and Tips for Nonfiction Writers

-

19-04-2023

Build Your Brand & Expand Your Reach with an Author Website: Tips & Tricks

-

17-04-2023

What is a Memoir? A Comprehensive Guide for Nonfiction Writers

-

12-04-2023

How to Write a Summary: Mastering the Art of Nonfiction Summarization

-

11-04-2023

Nonfiction Topics: Ideas to Ignite Your Creative Writing Journey

-

08-04-2023

Nonfiction Defined: A Guide for Aspiring Writers

-

06-04-2023

How to Format a Manuscript: The Ultimate Guide

-

04-04-2023

Types of Nonfiction: A Comprehensive Guide for Writers

-

23-03-2023

From Idea to Publication: How to Write a Book Proposal

-

15-03-2023

Mastering the Art of Writing in Third Person

-

13-03-2023

Good Book Ideas: Simple Concepts & Proven Formats for Nonfiction

-

11-03-2023

How to Write a Body Paragraph: A Guide for Nonfiction Writers

-

10-03-2023

Discovering Your Voice: How to Master Different Tones in Nonfiction Writing

-

07-03-2023

Things to Write About: Fresh Ideas to Ignite Nonfiction Writers’ Minds

-

05-03-2023

Persuasive Writing: Examples and Tips for Nonfiction Writers

-

03-03-2023

List of Strong Verbs: 300 Powerhouse Words for Nonfiction Writers

-

28-02-2023

How to Design a Book Spine

-

28-02-2023

7 Essential Steps for Outlining a Nonfiction Book

-

27-02-2023

Publishing: What Is an Imprint Page (and Why Do You Need It?)

-

16-02-2023

Developmental Editing for Nonfiction Writers: A Complete Guide

-

12-02-2023

Hook Writing: A Complete Guide for Nonfiction Writers

-

11-02-2023

The Importance of Typesetting: A Guide for Nonfiction Authors

-

09-02-2023

How to Improve Your Analytical Writing Skills: Tips and Guidelines

-

05-02-2023

Modern Fonts for Nonfiction Writers: A Comprehensive Guide

-

31-01-2023

How to Master Narrative Nonfiction – A Guide to Telling Great True Stories

-

30-01-2023

How to Quote a Quote: A Guide

-

24-01-2023

How to Get a Book Published (Step by Step)

-

24-01-2023

What Is a Paperback Book?

-

22-01-2023

The 5 Best Professional Fonts for Nonfiction Books

-

22-01-2023

When to Write Out Numbers In Nonfiction Books

-

21-01-2023

What Is Bias In Writing?

-

21-01-2023

Excerpt Definition and Meaning

-

27-12-2022

The Essentials of Writing: A Guide to Crafting Clear and Effective Content

-

24-12-2022

Writing the Perfect Non-Fiction Closing Statement: Tips and Tricks From an Expert

-

21-12-2022

Book Jacket: How to Create the Perfect Nonfiction Jacket

-

19-12-2022

What Are The Five Steps in the Writing Process?

-

14-12-2022

How to Get an ISBN for Free

-

10-12-2022

How to Cite a Quote from a Book

-

05-12-2022

How to Write a Book Dedication

-

02-12-2022

Pen Name: How to Choose One

-

26-11-2022

Why And How to Set Writing Goals

-

24-11-2022

Why Is It Important to Proofread Your Writing

-

23-11-2022

What Is Informative Writing?

-

22-11-2022

What Is a Paradox? (With Examples)

-

15-11-2022

7 Tips For Writing an Effective Personal Narrative

-

10-11-2022

How to Boost your Manuscript With a Writing Conventions Checklist

-

05-11-2022

What Is Parallelism And How to Use It in Nonfiction?

-

20-12-2021

A Complete Guide to Character Arcs: The Foundation of Fiction Writing

-

20-12-2021

Five Types of Conflict in fiction: And How to Write Them

-

17-11-2021

Different Types of Irony Used In Writing Fiction Books

-

17-11-2021

The Second Person: Powerful and Vulnerable

-

30-10-2021

Character Development: A Guide for Fiction Authors

-

29-10-2021

The 6 Essential Elements of a Story: A Guide for New Fiction Authors

-

07-10-2021

What is an Epilogue? 5 Tips to Write a Great One

-

06-10-2021

The Power of the First Person Point of View

-

25-06-2021

Business Writing Essentials: Types, Principles and Effective Skills

-

25-06-2021

Dialogue Writing: Strategies to Keep it Tight and Avoid Unnecessary Words

-

20-05-2021

Creative Nonfiction: What It Is, Why You Should Use It And How

-

07-05-2021

How Many Sentences Are In A Paragraph?

-

06-05-2021

5 Things You Should Know About Writing Realistic Fiction

-

05-05-2021

Punctuation Marks: A Guide for Nonfiction Writers

-

05-04-2021

How to Use Extended Metaphors: 7 Practical Steps

-

19-08-2020

What are the Different Types of Nonfiction Editors?

-

19-08-2020

How to Make a Book Cover for a Nonfiction Book

-

15-08-2020

What Are the Ideal Book Sizes for Your Nonfiction Category?

-

09-08-2020

How Do You Use the Active Voice in Nonfiction Writing?

-

06-08-2020

How to Print Your Amazon Book on Demand in 3 Easy Steps

-

21-07-2020

Learn How to Nail the Writing of a Nonfiction Paragraph

-

17-07-2020

How to Write the Perfect Introduction for Your Nonfiction Book

-

17-07-2020

Learn How to Write a Nonfiction Outline in 5 Easy Steps

-

17-07-2020

The Ultimate Book Design Guide for Nonfiction Authors

-

17-07-2020

What is a Transition in Writing? A Nonfiction Guide

-

13-07-2020

What is a Contraction in Writing? (Includes 129 Examples)

-

12-07-2020

What is the Passive Voice in Nonfiction Writing?

-

26-05-2020

How to Write a Biography in 8 Easy Steps

-

25-05-2020

How to Write Your Memoir in 9 Easy Steps

-

19-05-2020

711 Paragraph Transition Words for Nonfiction Authors

-

18-05-2020

How to Write an Autobiography that Sells in 10 Easy Steps

-

15-05-2020

How to Create an Amazon Author Central Account Step-by-Step

-

13-05-2020

How to Format a Nonfiction Book Outline

-

27-04-2020

Paragraph Introduction Examples for Nonfiction Writers

-

16-04-2020

Sentence Structure Primer for Nonfiction Authors

-

15-04-2020

Learn How to Cite Books in Nonfiction

-

14-04-2020

Standard Nonfiction Disclaimer for Copyright Page [With Examples]

-

13-03-2020

What is a Nonfiction Ghostwriter?

-

13-03-2020

The Top 5 Strategies of Nonfiction Writers

-

27-02-2020

The Guide to the CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

-

23-02-2020

How to Nail the Writing of Your Nonfiction Book Introduction

-

20-02-2020

The Top 5 Skills of a Nonfiction Writer

-

19-02-2020

How Long is a Paragraph in Nonfiction?

-

18-02-2020

How Many Different Types of Nonfiction Writers Are There?

-

14-02-2020

The Hidden Costs of Publishing a Nonfiction Book on Kindle

-

11-02-2020

The Best Creative Prompt Ideas for Nonfiction Writing

-

09-02-2020

How Can Writing a Nonfiction Book About a Topic Help My Business

-

06-02-2020

Nonfiction Publishing Success With KDP

-

05-02-2020

An Introduction to Nonfiction Paragraphs

-

03-02-2020

How to Master the Nonfiction Style of Writing

-

02-02-2020

The Best Words for Nonfiction Descriptive Writing

-

29-01-2020

How to Find the Best Editor for a Nonfiction Book

-

27-01-2020

How to Get a Nonfiction Book Printed and Bound for a Lot Less

-

24-01-2020

What Are the Rules for Writing a Paragraph that Engages With Readers?

-

21-01-2020

Nonfiction Book Publishing Companies Near Me

-

15-01-2020

How to Write the Perfect Nonfiction Introductory Paragraph (with an Example)

-

06-01-2020

How to Make a Book Cover Stand Out: 5 Best Practices for Nonfiction Authors

-

06-01-2020

Parts of a Nonfiction Book in Order: A Comprehensive List for Authors

-

06-01-2020

How to Get a Copyright for a Nonfiction Book

-

03-12-2019

21 Inspiring Quotes for a First-Time Nonfiction Writer

-

18-11-2019

A Comprehensive List of Punctuation Marks

-

15-11-2019

5 Elements That Will Make Your Book Back Cover Design Stand Out [With Examples]

-

14-11-2019

Great Blurb Examples for Books (A Guide for Nonfiction Authors)

-

13-11-2019

Paragraph Types with Examples: A Primer for Nonfiction Authors

-

12-11-2019

12 Nonfiction Short Author Bio Examples Plus 6 Steps to the Perfect Bio

-

05-11-2019

How to Make My Nonfiction Writing Better in 9 Easy Steps

-

01-10-2019

Legal Disclaimer Examples for Books

-

25-09-2019

Copyright Page: Everything You Need To Know and Why you Need It

-

25-09-2019

How to Create the Copyright Page of Your Book [with 6 Ready-to-Use Fiction and Nonfiction Samples]

-

22-09-2019

5 Great Reasons to Join a Writers Association

-

28-08-2019

The 4 Types of Editing Required to Create a Nonfiction Bestseller

-

14-08-2019

10 Must-Follow Editing Tips for Nonfiction Authors

-

07-08-2019

How to Find Ideal Writing Spaces: A Guide for Nonfiction Writers

-

01-08-2019

5 Book Editing Benefits for Nonfiction Writers

-

31-07-2019

How to Self Edit a Nonfiction Book in 7 Simple Steps

-

30-07-2019

How to Find the Best Nonfiction Book Writing Services

-

29-07-2019

Writing a Nonfiction Book for the First Time: Must Dos and Don’ts

-

28-07-2019

The Best Book Writing Advice for Nonfiction Authors

-

27-07-2019

The 5 Cardinal Book Writing Rules for Nonfiction Authors

-

26-07-2019

5 Steps to Develop Compelling Nonfiction Book Writing Ideas

-

25-07-2019

10 Editing Tips to Make Your Nonfiction Book Stand Out

-

24-07-2019

Looking for a Good Nonfiction Writing Skills Article? Follow These Guidelines

-

23-07-2019

How to Improve Your Nonfiction Writing Skills in 9 Easy Steps

-

22-07-2019

The Ultimate Book Writing Checklist for Nonfiction Authors

-

21-07-2019

The Ultimate Blueprint For Writing Your First Nonfiction Book

-

20-07-2019

How to Nail the Edit of a Nonfiction Book Cover

-

19-07-2019

The 12-Step Nonfiction Book Writing Process

-

18-07-2019

12 Critical Steps to Writing a Nonfiction Book

-

17-07-2019

How to Prepare for a Nonfiction Book Launch Event

-

16-07-2019

How to Find Book Cover Artists for Your Nonfiction Book

-

15-07-2019

How to Make a Nonfiction Book Cover in 5 Steps

-

14-07-2019

9 Book Cover Ideas that Will Turbocharge Your Nonfiction Sales

-

13-07-2019

The Ultimate Guide for Nonfiction Print On Demand Books

-

12-07-2019

10 Powerful Book Launch Ideas for New Nonfiction Authors

-

11-07-2019

5 Essential Book Writing Tips for Nonfiction Authors

-

10-07-2019

7 Must Use Book Layout Design Rules for Nonfiction Titles

-

09-07-2019

5 Book Cover Design Principles for Nonfiction Authors

-

08-07-2019

5 Great Book Title Ideas to Rock Your Nonfiction Sales

-

07-07-2019

5 Benefits of Self-Publishing on Amazon for Nonfiction Authors

-

06-07-2019

The True Cost of Self-Publishing on Amazon for Nonfiction Authors

-

05-07-2019

Self Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: Pros and Cons

-

04-07-2019

Self-Publishing Pros and Cons: The Ultimate Guide for Nonfiction Authors

-

03-07-2019

14 Self-Publishing Tips to Turbo Charge your Nonfiction Book Sales

-

02-07-2019

How to Self Publish with Kindle (A Guide for Nonfiction Authors)

-

01-07-2019

Self-Publishing on Amazon: Pros and Cons for Nonfiction Authors

-

30-06-2019

How to Self Publish on Amazon: A Guide for Nonfiction Authors

-

29-06-2019

How to Self-Publish Nonfiction with Success

-

28-06-2019

Self-Publishing Quotes – What to Expect for Your Nonfiction Book

-

27-06-2019

How to Hire A Ghostwriter to Write Nonfiction that Tips the Scales

-

26-06-2019

Want to Hire a Writer for a Nonfiction Book? Start Here

-

25-06-2019

3 Steps to Follow Before You Find a Nonfiction Ghostwriter

-

24-06-2019

How to Get a Copyright for a Nonfiction Book in 4 Easy Steps

-

23-06-2019

What’s the Copyright Cost for a Nonfiction Book?

-

22-06-2019

How to Copyright a Book and Protect Your Work from Plagiarism

-

21-06-2019

5 Tips to Hire a Ghostwriter to Work with Nonfiction Authors

-

20-06-2019

How to Hire a Professional Ghostwriter to Write your Nonfiction Book

-

19-06-2019

How to Find the Best Freelance Writing Service for Nonfiction

-

18-06-2019

Need an Editor for Your Nonfiction Book?

-

17-06-2019

How to Find a Nonfiction Book Editor

-

16-06-2019

All You Need to Know About Nonfiction Developmental Editing Rates

-

15-06-2019

How to Find the Best Copy Editing Services for Nonfiction Authors

-

14-06-2019

Nonfiction Book Editors Near Me

-

13-06-2019

How to Properly Vet an Editing Company

-

12-06-2019

What are typical proofreading rates for nonfiction books?

-

11-06-2019

If You Can Afford it, Hire a Book Writer: 9 Compelling Reasons for Nonfiction Authors

-

10-06-2019

How to Find the Best Content Editor for Your Nonfiction Book

-

09-06-2019

Why You Need Developmental Editing Done on Your Nonfiction Book

-

08-06-2019

Learn How to Promote a Nonfiction Book on Social Media with Success

-

07-06-2019

How Do I Promote My Self-Published Nonfiction Book for Top Sales?

-

06-06-2019

5 Key Marketing Ideas Every Nonfiction Authors Should Implement

-

05-06-2019

Book Marketing Companies You Should Definitely Avoid

-

04-06-2019

20 Powerful Ideas to Promote Your Nonfiction Book

-

03-06-2019

How to Create a Book Marketing Plan that Turbo Charges your Sales

-

02-06-2019

How to Hire the Best Book Promotion Services for Nonfiction Authors

-

01-06-2019

Learn How Hiring a Marketing Consultant Will Help You Sell a Lot More Books

-

31-05-2019

How to Get Reviews on Amazon for Your Nonfiction Book

-

30-05-2019

How to Promote Your Book to Rank High on Amazon Nonfiction

-

29-05-2019

How to Find the Best Book Marketing Services for Nonfiction

-

28-05-2019

Learn How to Market a Nonfiction Book to Get Solid Results

-

27-05-2019

7 Highly Effective Book Promotion Tactics for Nonfiction Authors

-

26-05-2019

Write Your Own Book and Become an Expert: 11 Reasons Why You Should

-

25-05-2019

The 5 Steps of Writing a Book Outline to Maximize Nonfiction Sales

-

24-05-2019

The Best Self-Publishing Sites for Nonfiction Authors

-

23-05-2019

Make Your Own Book and Add 7 Revenue Streams to Your Business

-

22-05-2019

Follow This Writing Plan to Create Your First Nonfiction Book

-

21-05-2019

How to Make a Book That Generates High Paid-Speaking Fees

-

20-05-2019

Write a Book And Dominate Your Industry: 11 Game-Changing Benefits

-

19-05-2019

Learn 5 Easy Steps to Self-Publish a Book If Your Nonfiction Manuscript Is Ready

-

18-05-2019

How to Self Publish a Book in 7 Steps: A Guide for Nonfiction Writers

-

17-05-2019

How Much Does It Cost to Self Publish a Nonfiction Book that Sells Well

-

16-05-2019

7 Time-Saving Steps to Publish a Nonfiction Book in Record Time

-

15-05-2019

Self Publishing on Amazon KDP: Everything Nonfiction Authors Need to Know

-

14-05-2019

How to Find The Ideal Nonfiction Book Publishing Company for You

-

13-05-2019

What to Look For in a Top Book Self-Publishing Company

-

12-05-2019

Self-Publishing Companies to Avoid: 7 Warning Signs to Look Out For

-

11-05-2019

5 Book Cover Maker Mistakes to Avoid When You Design a Nonfiction Cover

-

10-05-2019

The Top 7 Book Structure Templates for Nonfiction Authors

-

09-05-2019

Learn How to Outline Your Nonfiction Book in 10 Easy Steps Like the Pros

-

08-05-2019

5 Mistakes to Avoid When You Lay Out a Nonfiction Book

-

07-05-2019

7 Book Planning Best Practices Used By Nonfiction Pro Authors

-

06-05-2019

Learn the Best Book Structure to Maximize Nonfiction Sales

-

05-05-2019

7 Simple Steps to Writing a Powerful Nonfiction Book

-

04-05-2019

Learn the Ultimate Book Format Guidelines for Nonfiction Authors

-

03-05-2019

How to Format a Manuscript Like A Pro (A Guide for Nonfiction Writers)

-

02-05-2019

I Want to Write a Nonfiction Book, Where Do I Start?

-

01-05-2019

Learn How to Write Nonfiction: 12 Tips from The Pros

-

30-04-2019

How to Use Expository Writing in Nonfiction to Establish Your Expert Credentials

-

29-04-2019

5 Narrative Writing Steps for Nonfiction Books

-

28-04-2019

How To Use Descriptive Writing To Write A Book That Readers Can’t Put Down

-

27-04-2019

10 Next-Level Persuasive Writing Strategies for Nonfiction Authors

-

26-04-2019

How to Use All 4 Writing Styles to Create an Exciting Nonfiction Book

-

25-04-2019

10 Tips for Writing a Bestselling Nonfiction Book

-

24-04-2019

7 Key Writing Strategies Used by Bestselling Nonfiction Authors

-

23-04-2019

5 Professional Paragraph Writing Tips for First-Time Authors

-

22-04-2019

The 7 Key Rules for Writers of Outstanding Nonfiction Books

-

21-04-2019

How to Become a Great Book Writer in Business Nonfiction

-

20-04-2019

How to Find the Ideal Writing Coach for Your Nonfiction Book

-

19-04-2019

The 10 Must-Have Writing Skills For Nonfiction Authors

-

18-04-2019

How to Hire the Ideal Professional Writer for Your Nonfiction Book

-

17-04-2019

The Best Book Writing Apps for Nonfiction Authors

-

16-04-2019

How to Outline a Nonfiction Book in 5 Simple Steps

-

15-04-2019

How Much Does a Ghostwriter Cost to Write a Book for Your Business?

-

14-04-2019

How to Find a Great Nonfiction Book Editor and Filter Out the Bad Ones

-

13-04-2019

10 Nonfiction Book Layout Tips That Will Glue Your Audience to the Page

-

12-04-2019

How to Write a Compelling Book Introduction That Will Move the Needle

-

11-04-2019

How to Mind Map a Book: A Step-by-Step Guide for Nonfiction Authors

-

10-04-2019

How To Come Up With Nonfiction Book Ideas That Sell

-

09-04-2019

How to Grow Your Business Writing a Nonfiction Book

-

08-04-2019

The Most Effective Writing Exercises for Busy Business People

-

07-04-2019

How to Come Up With Killer Book Titles for Your Nonfiction Book

-

06-04-2019

Learn 10 Powerful Writing Habits to Fast Track Your Nonfiction Book

-

05-04-2019

How Long Does it Take to Write a Book to Help Grow Your Business?

-

04-04-2019

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps: A Must-Read Guide for Nonfiction Authors